Empty Bunkers and Hot Homes: Why thousands of UK tenants are now joining the ‘Right to Sue’ movement this winter

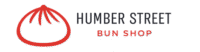

40 a.m. in a North London kitchen and you can see your breath. The kettle rattles, a strip of black mould crawls along the window seal, and the group chat pings with a link: “Template letter to sue your landlord.” That’s how this winter feels — brisk, brittle, and suddenly, very bold.

The woman who sent the link is a nurse on nights. The guy replying is a courier who sleeps with a dehumidifier growling at his feet. Someone else posts a screenshot: a small payout, yes, but also a legally binding promise of repairs. It smells like wet plaster and stubborn hope. Across the city, across the country, something once private is becoming public. A confrontation is brewing.

Empty bunkers, hot homes: the winter paradox

Walk any riverfront after dark and count the silent balconies. Investment flats turned into storage units for capital; empty bunkers, lit by the blue haze of nothing. Then head two streets inland and feel the rental market radiate: overheated by bidding wars, cranked by scarcity, thick with condensation and worry. The word “home” is doing a lot of work.

In Manchester, Maya kept a “cold diary” on her phone: dates, temperatures, photos of her toddler’s steaming breath indoors. She joined a tenants’ chat, downloaded a letter, and pushed for repairs under the Homes Act. Three weeks later, a contractor arrived with fans, new vents, and a plan. Compensation wasn’t life-changing, but it paid the winter coat and stopped the cough.

What’s changed isn’t just the weather. Rents have risen faster than wages, energy bills still bite, and vacant dwellings make headlines while working families shiver. The public learned new words — “excess cold,” “fitness for habitation,” “pre-action protocol.” Grassroots groups show people how to log evidence and press send. Landlords still hold keys, but tenants are finding leverage.

What is the ‘Right to Sue’ — and how it’s being used

The phrase sounds dramatic, yet it’s grounded in law. Tenants in England and Wales can seek repairs and damages when a property is legally “unfit” — think serious damp and mould, persistent leaks, broken heating, unsafe electrics. The route runs through the Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act and housing disrepair rules, not a Twitter storm. It’s paperwork, proof, and deadlines.

Here’s the new winter ritual. Tenants start a paper trail: photos with dates, humidity readings, logs of symptoms, emails requesting repairs. They send a Letter Before Action, quoting the right clauses and asking for a timetable of works. If progress stalls, many escalate via the council’s environmental health team or file a claim with a local solicitor. No drama, just process.

One big accelerant has been visibility. Social feeds now circulate templates and stories of small wins: new boilers fitted, roofs patched, rent abatements for months of unusable rooms. Add in the moral shock after high-profile mould tragedies and the traction of Awaab’s Law in social housing, with clearer time limits for fixing hazards. People realised the rules aren’t abstract. They’re levers.

How tenants are turning frustration into action

Start small, start methodical. Keep a 30-day evidence journal: two photos a week from the same angles, short videos showing dripping or cracked seals, a cheap hygrometer screenshot at morning and night. Log every repair request in writing and ask for a schedule of works with dates. A tidy folder of facts beats a long, emotional rant every time.

Common missteps? Stopping rent outright, venting only by phone, or binning receipts for dehumidifiers and heaters. Put it in writing, keep it calm, and capture everything that shows loss of amenity. We’ve all had that moment when you assume “it will sort itself” — winter isn’t that season. Let’s be honest: nobody meticulously documents their home every day. So build the habit with reminders and a simple template.

If you can, speak with neighbours. Shared evidence in the same building strengthens a pattern and can nudge councils faster.

“What wins these cases is boring consistency,” says Lena, a housing solicitor in Leeds. “Dates, photos, reports — not rage.”

Here’s a quick kit many renters now swear by:

- One folder per issue: damp, heating, leaks, electrics.

- Monthly utility and repair-cost receipts clipped in.

- Letter Before Action template referencing the Homes Act.

- A short summary timeline you update weekly.

- Backups: email yourself the lot once a month.

Landlords, councils, and the rest of us: what this winter signals

Behind the headlines sits a quiet shift in power literacy. Tenants aren’t waiting for luck; they’re learning processes and pressing levers. Councils, stretched thin, are triaging hazard by hazard. Landlords balancing mortgages and repairs are discovering that prevention is cheaper than a claim. The shared interest is simple: warm, dry, safe rooms that don’t make people ill.

There’s also a story about the nation’s housing metabolism. Empty “bunker” flats gathering dust, “hot” rentals cooking the market, and the everyday cold drama in Britain’s older stock collide into one winter picture. The legal route isn’t a cure-all. It is a pressure valve. If thousands use it, standards lift by osmosis. Not overnight. Not evenly. Yet visibly.

Some readers will feel the tug to act. Others might pass this on to a friend with that stubborn black bloom in the corner of their ceiling. A city’s health is hard to measure, but you can feel it in the first breath you take at home. This winter, tenants found a phrase that fits in a message bubble and a file that fits on a phone. The next part is what happens when everyone knows how to use it.

| Key point | Detail | Interest for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| What “Right to Sue” really means | Using existing law to force repairs and claim damages for unfit housing | Turns frustration into a practical route with deadlines and outcomes |

| What counts as “unfit” | Serious damp/mould, excess cold, leaks, unsafe electrics, broken heating, poor ventilation | Helps you decide if your situation is likely to qualify |

| How to build a winning file | Photos with dates, logs, receipts, expert reports, clear timelines of requests | Makes your case harder to ignore and faster to resolve |

FAQ :

- Who can use the “Right to Sue” route?Most private and social renters in England and Wales with a tenancy agreement can bring a claim about unfit conditions. Lodgers and some temporary arrangements may be different.

- Do I need a lawyer to start?No. You can begin with a written repair request and a Letter Before Action. Many people then get advice from a housing charity or solicitor if the landlord doesn’t act.

- What evidence helps the most?Dated photos, humidity and temperature readings, medical notes if relevant, repair invoices you’ve paid, and a timeline of every message sent and received about the issue.

- Could my landlord evict me if I complain?Retaliatory eviction is restricted, and council enforcement can offer extra protection, but the risk varies by case. Keep everything in writing and seek advice early.

- What outcomes are realistic?Repairs ordered within a set timeframe, rent reductions for the period you lost use of rooms, and compensation for distress or belongings damaged by disrepair.